coriolanus: a man for our times

what shakespeare's unsung tragedy can teach us about authenticity and honour on the eve of the greatest political pantomime on earth

Earlier this month I saw a preview of Coriolanus at London’s National Theatre and then later the same week, A Face In the Crowd, a new musical adaptation of the film at the Young Vic. As often happens, by sheer coincidence, the two plays turned out to be thematically linked. Both are about men who rise to power and fame on their own merits only to squander it by behaving like spoilt brats. Apart from that the two plays aren’t remotely comparable but since you didn’t ask, I preferred the former, though it did suffer from a lack of catchy show tunes by Elvis Costello (which were good, but not so good they saved the latter production, more on that a bit further down).

I haven’t seen Coriolanus live since I was an adolescent theatre-student on the annual field trip to Stratford, Ontario (yes Canada has a quaint nouveau version of everything, it’s our cultural contribution to the world). The first time, the play made little impression on me, which suggests I was probably stoned. It wasn’t til I read Coriolanus at university, in particular the famous, pivotal scene in which he refuses to display his battle wounds to the crowd, that it’s brilliance became clear. One of the less worshipped tragedies, it’s mostly action and dialogue with little reflection or pause. But that particular scene has stayed with me, over the decades I’ve returned to it, and seeing it staged live was a revelation and delight. The more cranky-pants critics judged David Oyelowo’s performance a bit flat, but I found it riveting. His Coriolanus was taciturn, cool, officious. He seemed oddly detached from his tiger mother and sentimental wife, a man capable of greatness not in spite of his lack of empathy or interest in others, but because of it. It’s true, I think, Oyelowo made little effort to charm his audience, but this was clearly intended and dovetailed neatly with the play’s pressing questions: How much can we, ‘the people,’ reasonably expect of our leaders? In an inherently corrupt system, what is honour actually worth? And most crucially, how does it differ as a value from its vague modern substitute, authenticity?

Trump’s presidency ushered the west into a new democratic era of celebrity nationalists who seduce their respective electorates by turning free-thinking citizens into fans. But Coriolanus is no harbinger. He’s flawed in a more original way. Rather than being a vain, malevolent opportunist, he’s the inverted mirror image of one. The broadly accepted scholarly view is that it’s a play about pride, but I think this is simplistic. Coriolanus isn’t so much proud as genuinely unyielding. And yet, for all his unflinching honour he still winds up dying a traitor. This is what makes the play so uniquely good. As a hero, he doesn’t change. He won’t evolve. He’s not a waffler or a compromiser — he’s a man of action, a warrior — and his inability to bend is what finally does him in.

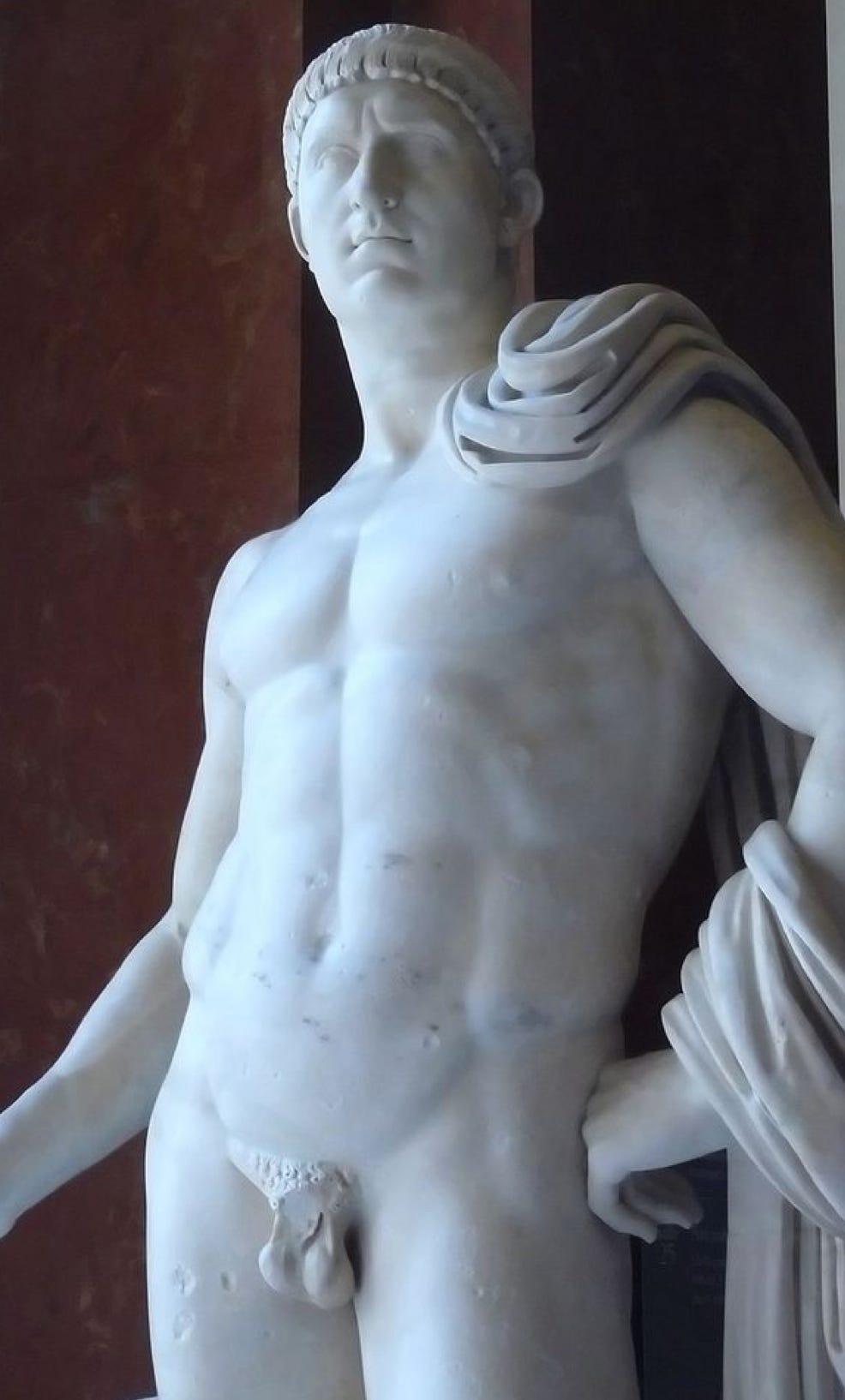

Plot recap, sorry! Coriolanus tells the story of Roman warrior who returns home to assume his mantle of power but falls at the last hurdle by refusing to subject himself to the ritual of showing his wounds to the adoring stadium crowd. For this breech of the symbolic cultural pantomime, he’s rejected by masses and pushed out of his own caucus by opportunists and, ultimately, banished from Rome. Once an outsider, Coriolanus manages to team up with the only guy on earth he truly respects — his former nemesis — and together they lead an insurrection on the great city state. It goes well, until it goes badly wrong.

To interpret it as a cautionary tale for the Trump era or a riff on cancel culture (as some critics did) is massively over-thinking it. Plot-wise, Coriolanus is hardly intricate. It’s like one of those tail-end-of-the-zeitgeist-superhero-epics, the final sequel in some tired Marvel/DC franchise in which the studio, having run dry on ideas, decides to team up the hero and uber-villain against the world and press ‘go.’ This makes it sounds awful, but because it’s Shakespeare, it still somehow manages to be genius with important stuff to tell us about ourselves and the state of democracy today.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Juvenescence with Leah McLaren to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.