It’s been four months now since our little world was turned upside down. Nearly three since my sons have had any substantive contact with their dad. In that time the three of us have celebrated one birthday, one Halloween and one Christmas. Frank has lost two teeth, won Dojo Champion of the week, invented six new dance moves and discovered a newfound passion for tidying the house. Solly, meanwhile, has acquired his first iPhone and with it a portal to the world of tween snapchat, scored dozens of primary school playground goals, started a regime of medicine ball workouts and morning protein shakes and watched all five seasons of Cobra Kai twice. London has gone from late-summer balm to autumn’s honied light to the clammy dark of December to clear, crisp and bright — an extended late January cold snap.

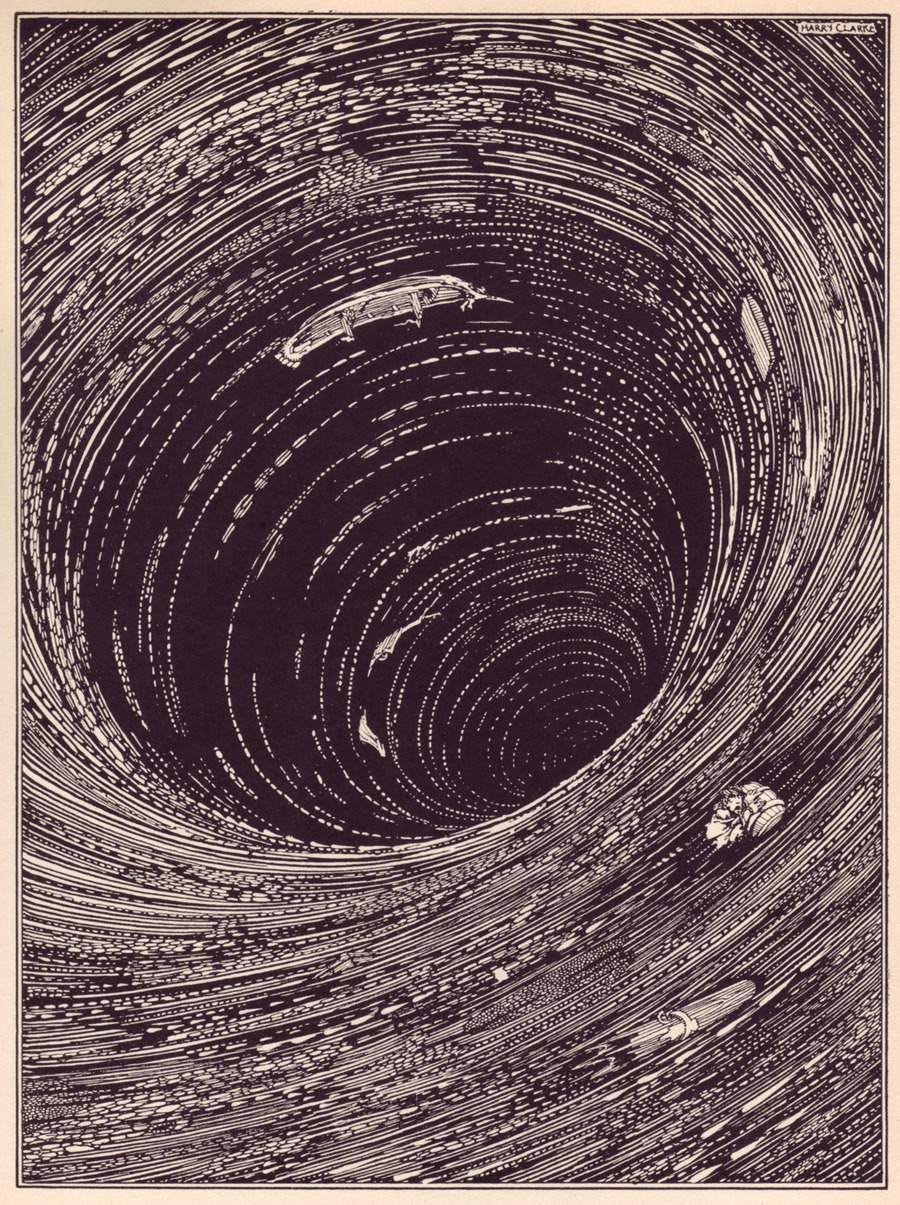

The months come and go, milk teeth fall out and big ones grow back in their place. Even when you find yourself trapped in a vacuum, the matter outside the sucking sound does not cease to exist. You can exist in a black swirl of nothingness for only so long before the world pushes in.

Four months in and — I still cannot quite believe I am writing this — I still have no substantive answers. No information to relay. Zip, zilch, zero. No indication how things might play out. I’ve run out of savings and am applying for universal credit and legal aid, and failing that an eye-watering litigation loan. Soon, I suppose, our problem, our “matter” will be before the courts. I’m told there is no other choice. Court is the one place my husband and I promised each other solemnly even at our lowest ebb that we would never go. For private family matters like ours court is like pissing in the wind. No one wins but the lawyers and even they don’t enjoy it. I desperately did not want it to go this way, nor did he. What reasonable person would? But what does he want? Where is he? How is he? Who knows? In the information vacuum nothing exists but the absence of knowledge. Every strategy is based on uncertainty. All you know is what you don’t.

The hardest part is having nothing to tell the boys. The looks on their faces when they work up the courage to ask, ‘Where is he?’ or ‘When will he get better?’ or simply, ‘What’s going to happen Mum?’

I’ve dispensed with platitudes at this point. My fingers are blistered and singed with the sulphurous match-stick-ends of false hope. Now I tell my sons the truth when they ask their open questions: I’m sorry, I don’t know. I’m sorry, don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know.

Does anyone know?

Yes. Lots of people.

Why won’t they tell us?

I don’t know.

How long can it go on like this?

I don’t know.