When we bought this house ten years ago it came with a folder containing all the old handwritten Victorian title deeds and survey maps of the area right back to the 1897 when the the Warden and College of All Souls Oxford leased it to Mr. Richard Crowle for the yearly rent of five hundred pounds and ten shillings. The old deeds are enormous, imposing — prior to typewriters, super-sized stationary was a matter of Great Import. They are beautiful things, written in fountain pen and adorned with flirty feminine details that undermine their officiousness — blood red wax seals and silky green bows. Friends have advised me to frame them but I couldn’t, I can’t, it would be wrong — they belong to the house. Instead I sit with them sometimes, run my fingers over them, thinking of the people who used to be in these rooms where I now live contentedly with my loved ones.

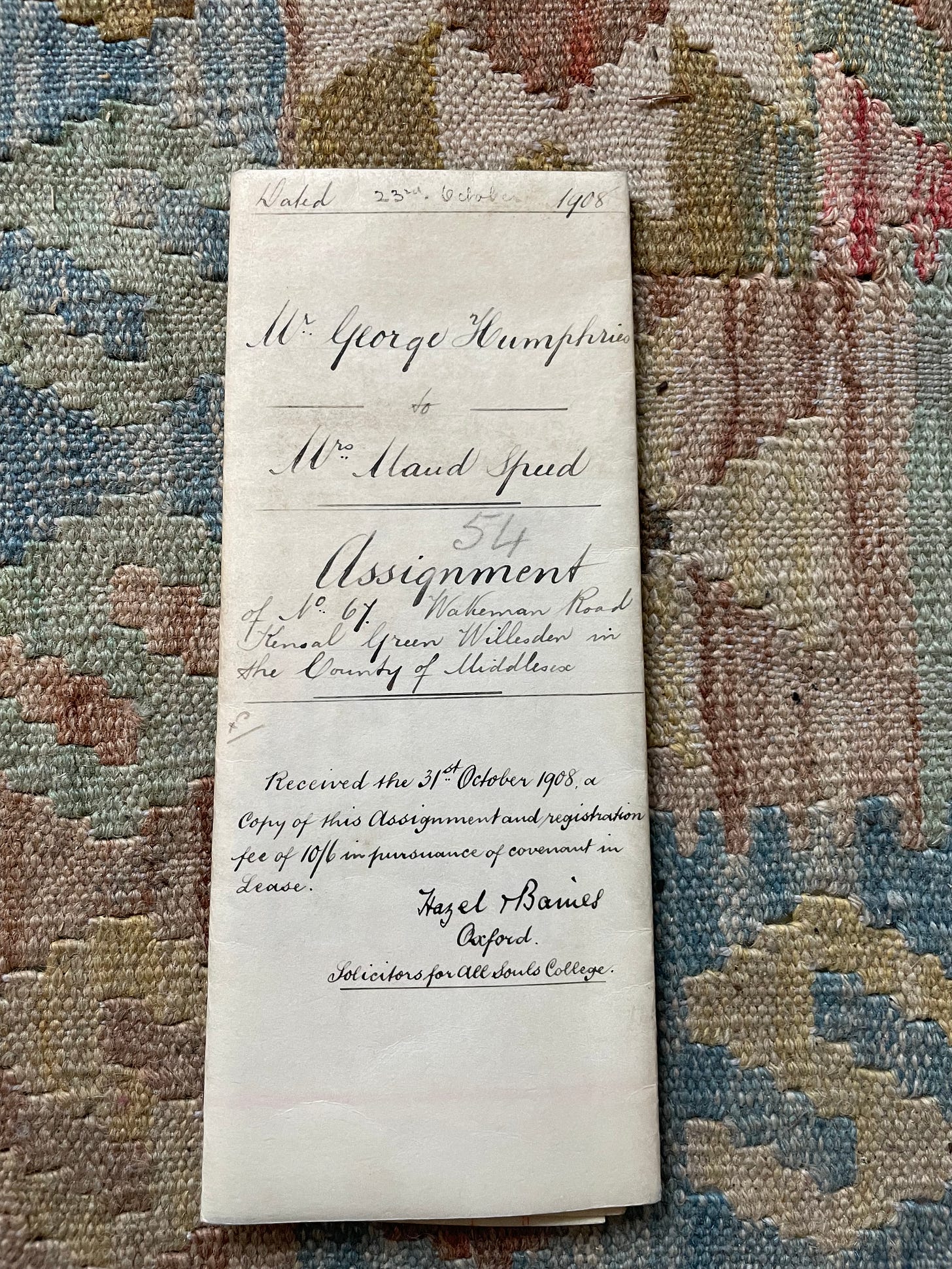

In 1908, George Humphries, a local laundryman, sold the house for one thousand nine hundred and eight-seven pounds to one Mrs. Maude Spud, who purchased it solely despite being listed as a “married woman.” Perhaps she was widowed or “fallen” — a bolter, a tart, abused or abandoned. Her name does not suggest riches (sadly for England there’s no Earldom of Spud). It’s possible she was divorced. The practice was legalised in the UK in 1858, but more crucially, in 1882 the Married Woman’s Property Act made it legal for a woman like Maud to own and control their own property. She lived in this house for only a few years before the place was again sold by a man named Samuel Spud, who was presumably either her absent-returned husband, her brother or (more likely) her surviving son. Probably she died here. Victorians were born and died at home mostly. Oddly there’s no record of how the house was transferred from Maud to Samuel. Perhaps it did not matter to the lawyers? It matters to me, though. I scan the tombstones for her name on my runs through Kensal Green cemetery.

Maud’s been on my mind lately because I’ve been reading Zaidie Smith’s latest, The Fraud, which is set mostly around in here, in Kensal, during the time when Maud lived here. It’s copiously researched, but in a subtle way that would only be apparent to someone who’s lived in Kensal a long time. Local landmarks, memorable graves and grand forgotten houses are mentioned by characters in passing. For most readers these details would have little meaning, but because this is my place, the place where my sons are from, these glancing descriptions send shivers through my body like astonishing coincidences.

How oblivious most of us are most of the time — not just to our own mortality (which is understandable), but to the obvious fact that not very long ago other people, mostly dead ones, lived where we live. I wonder why we don’t think about them more often. If geography is destiny why are we so collectively incurious about what happened to the people in the places that matter most to us?

I say “incurious” because unlike the present or the future, which are impossible to fully fathom, history can at least be researched. Things actually happened here — they did! If we dig in the right places there are records and surveys. I suppose there’s the possibility we might find out awful, but grisly murders happen rarely. More likely what we’d find are stories of people like us. People who lived everyday lives full of anguish and joy and nonsensical worry over future catastrophes that in the end did not happen.

I suppose this is why novelists exist and also why writers of fiction will never be replaced by robots who don’t wander aimlessly through neighbourhoods, get distracted by tombstones and spend three years in an archive researching the life of a dead woman and imagining how she felt while shopping for milk in 1911. The dead have so much to tell us and novelists like Smith are their self-appointed conduits. We live in their houses and shop in their markets, send our kids to their schools, convalesce in their hospitals and eventually we will be buried alongside them. The thought takes my breath away sometimes, especially in London: All of these buildings were built by dead people and yet here they still are, standing and occupied and used by the living.

(The next time someone tells you the whole world’s going to shit, just pause and think about that for a moment.)

Alone in the evening, once the boys are asleep, I can feel them around me. Maud and the others.

As housemates go, ghosts are good value, they don’t eat the good Manchego or leave tea bags in the sink; when the nights are long in December they’re amiable company round the wood-stove. A nominally married woman in “complicated circumstances” can’t really go down to the pub unaccompanied without fear of gossip. Not much has changed in Kensal on that score since Maude’s time. In any case I prefer their whispered old stories to talking politics with blowhards.

What have they told me? Well let’s see...