Do you ever find your life takes on an accidental theme? A random mini-trope that manages to weave itself, like a golden thread, into the humdrum flannel of daily life?

For me, it happens all the time. For no apparent reason I’ll suddenly be seized by a passion and hurl myself into an arcane subject for weeks, sometimes months. I suspect it’s a function of my early career, during which I worked as a general-interest columnist and feature writer for a the “soft sections” of a Saturday broadsheet. Each week, I was required to immerse myself in the minutiae of some bizarre, often hilariously half-baked, social trend (strip club date nights, normcore, Y2K survivalism — none of which actually happened, not that it stopped us from writing about it!), then with the help the testimony of a handful of sources, whom we called “real people,” (the pre-data saying on the Style desk was “three examples makes a trend”) a couple of “numbers” (plucked from some dubious survey or, worse, a press release), perhaps if you were feeling really ambitious, a plausible quote from a “pointy head” (boring expert with a few letters after his name), then generate several hundred — or thousand — cogent words on the subject. Lather, rinse, repeat!

These days theming is a habit I barely notice. I’ll pick up a second hand book on the secret life of fungi, then find myself watching a documentary on the history morel foraging in France, then I’ll find myself cycling down to see the Portobello Market Mushroom Man, buying a bag of wild chanterelles I can’t afford then spend most of an afternoon constructing a luscious wild mushroom galette, which my children will look at and gag.

More often than not my passing mini-tropes take the form of book binges. I’m a compulsive reader, from a family of compulsive readers, married to a compulsive reader, which is a problem because one day all the shelves in our house will collapse and we’ll be buried alive. The most recent binge, as the title of this letter suggests, is sick bitches, by which I do not mean rabid dogs or hot babe serial killers but females of the human and animal variety who find themselves mistreated or otherwise infirm. It all started with a thoughtful gift from my sister-in-law last Christmas: A big fat hardback copy of Elinor Cleghorn’s gorgeously designed and rigorously researched Unwell Women: A Journey Through Medicine and Myth in a Man-Made World — a brilliant (and shocking) social history of the gross abuse and misunderstanding (much of it wilful) of female bodies and minds at the hands of the medical establishment since the birth of modern medicine.

After that, I picked up Sarah Polley’s magnificent memoir in essays, Run Towards the Danger (published in the UK this week). What began as a seemingly unrelated read, soon revealed itself as a riveting and intelligent variation on the sick bitches theme, specifically the concept of “malingering” (that much-abused catch-all applied to many of the so-called mystery illnesses associated with womanhood). Polley’s book tells the story of her young life as a reluctantly famous Canadian child star, the tragic (largely unprocessed) early loss of her mother, a teenaged sexual assault she suffered at the hands of the disgraced broadcaster Jian Ghomeshi as well as her agonising decision not to come forward, the traumatic birth of her first child and finally, a freak accident which resulted in a midlife concussion that left her virtually bedridden and unable to work. Through the fragmented kaleidoscope of memory, Run Towards the Danger is Polley’s attempt to unpick the complicated truth-puzzle of girlhood, motherhood, sexuality and trauma.

Polley was followed by four brilliant novels on the trot, all of them by women and concerned with the female experience of science, illness and health. They were, in no particular order, Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi (which I enthused about at length in last week’s Juvenescence, followed by Meg Mason’s devastating (and devastatingly funny) first novel Sorrow and Bliss — a truly ingenious take on mental illness through the prism of an impossible, exasperating woman you cannot help but love.

Rounding off the string of sick fictional bitches was Klara and the Sun, latest from Kazuo Ishiguro, which I’d had on pre-order for months (if I could pre-order all of Ishiguro’s works until one or both of us died, I would). He’s a master obviously, a Nobel laureate, the king of emotional subtlety and restraint, but I had no idea what lovely, generous, funny and generally-chilled-out human he was (is) until I happened upon his recent interview with the British comedian and broadcaster Adam Buxton.

(As an immigrant to the UK, I often feel a bit like Klara, the AI-bot protagonist of Ishiguro’s novel, because I’m forever trying to work out the cultural references. At parties my inner monologue runs like this: Wait, who’s Billy Connelly/Cyrille Regis/Aisling Bea again? What was the Profumo scandal about? Who are the Gold Blend couple? Where the fuck is Ripon? This is all to say that Buxton’s interview podcast, which features primarily British writers, thinkers and comedians, many of whom are household names in the UK but lesser-known quantities offshore, was a revelation. Mining his archive, and other similar podcasts like Annie Macnamanus’s Changes and Sam Baker’s The Shift, to name a couple — please suggest more! — has been an invaluable a source of British contemporary pop-cultural knowledge, along with the seemingly-bottomless back catalogue the BBC’s Desert Island Discs.)

Ishiguro I had obviously heard of even before I arrived in Britain — I’m not a complete colonial rube. Late last year, in fact, I re-read his 2005 novel Never Let Me Go, which in turn prompted me to re-watch The Remains of the Day and both seem to have improved with age, if that’s even possible. It’s intensely comforting to me when a book or a movie proves just as much of a pleasure revisited as on the initial encounter — like one of those precious old friendships where you know you can pick up the conversation years later exactly where you left off.

After the heartbreak of Klara, Bonnie Garmus’s larky and lauded first novel Lessons in Chemistry provided some intelligent and much-needed comic relief. (I should add that like Polley, Garmus was kind enough to blurb my fourth-coming memoir, which is also bitch-related in that it’s about mothers and daughters — but let’s leave that theme for another day, shall we?). Set in California in the 1960s, it tells the unlikely yet compellingly believable story of a thwarted female scientist who accidentally becomes a Julia-Child-like TV cookery goddess of her time.

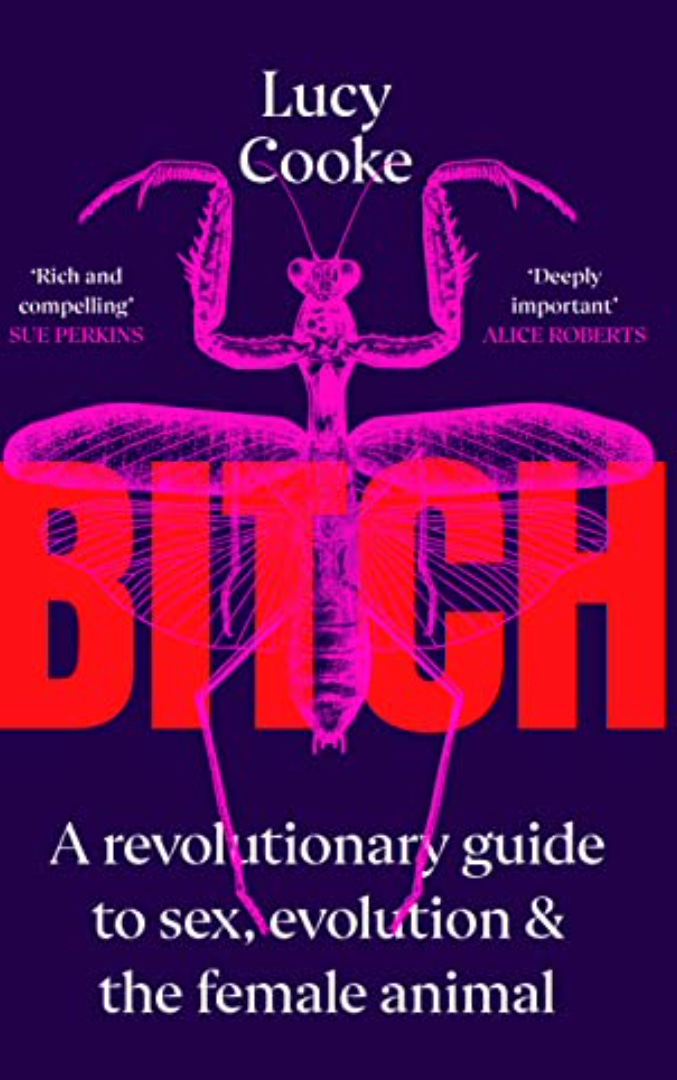

Last but not least in my accidental sick-ass-bitch theme and the seminal (pun intended) inspiration for this newsletter, is Lucy Cooke’s stunning biological polemic Bitch: A Revolutionary Guide to Sex, Evolution and the Female Animal. Reading it I felt the profound sense of recognition you get when listening to a well-evidenced argument you kind of already knew but hadn’t been able to fully articulate yourself (inner bitch monologue: Finally! Thank you! What she said!).

In essence, Bitch does for science what Caroline Criado Perez’s Invisible Women and Unwell Women did for data and medicine. By revealing the aggressive, selfish, brutal and unapologetically engorged clit-wielding behaviour of a myriad of Mother Nature’s bitches (moles, hyenas, spiders, fish, to name just a few), Cooke offers a ferocious, urgent and meticulously researched debunking of the received scientific wisdom that the female sex is inherently passive and nurturing compared to our (apparently dominant, aggressive) male counterparts. Not only does she systematically dismantle these pernicious essentialist stereotypes (lazily perpetuated by Darwin on down), she reveals them as heavily biased at best and at worst, knowingly fraudulent. The genius of Cooke’s argument is that she restricts her observations solely to the matter biological sex, steering carefully clear of the social construct of gender. In the objective biological study of animals, of course, gender is utter nonsense — a seductive human invention, perhaps, but as inapplicable to dolphins or cheetahs as money or religion. In this way, Bitch powerfully demonstrates how the lazy conflation of sex and gender laid the pernicious foundation for modern patriarchy, and furthermore, how we might free ourselves from the clutches of this binary thought trap not through cultural warfare, but through the acceptance of biological fact.