small pleasures: on the unexpected joy of mending

in praise of fixing what we can, while we can, tenderly

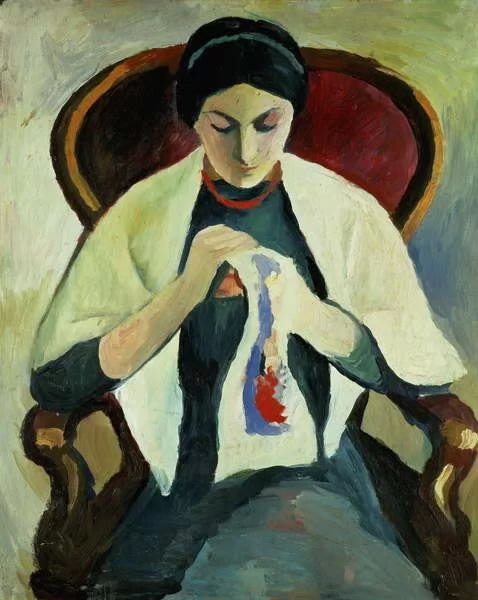

This morning after the school run I sat down on the yellow kitchen sofa and set about doing something I’ve been putting off for months: mending a lost button that had fallen off my favourite silk pyjama top.1

It was fussy, menial work, but and not entirely mindless. As I sewed (clumsily, sloppily, cursing myself for having skipped home economics in favour of autoshop in high school) I listened to a BBC radio program about industrial decline.

The panel was a predictable grab bag of pointy heads. The historian Sam Wetherell, author of Liverpool and the Unmaking of Britain, talked about the little known history of deportation and discrimination against the early migrant dock workers who, for a time in the 1800s, helped to make the city a beacon of industrial affluence, a dry but knowledgeable Chinese economic expert from Chatham House, and some TV writer I’d vaguely heard of flogging the most recent Post-Office-Scandal-style Netflix series on an industrial-waste-scandal in Midlands.

Tedious and worthy listening for a tedious worthy task, I thought grimly. I thought about changing it to music, then decided it was apropos listening for a dreary Monday morning in mid-February.

I threaded and rethreaded my needle, squinting and managing to prick myself in the process. I swore, half-listening to the voices on the radio, knowing I would never read a book about the history of the Liverpool docks or watch a program about Corby in the 90s. All the same, I kept mending and listening.

Just get it over with, Leah.

When I’d finally reattached the lost button successfully (loose threads everywhere, who gives, it was sturdy), I paused for a moment and consider my work. You see, now that I’d finally taken the time to look closely at the pyjama top, I noticed some of the other buttons were starting to come loose as well. It occurred to me if I didn’t mend them in advance, they too would eventually pop off and be lost, at which point I’d either end up tossing out a pair of perfectly good silk pyjamas (which would be stupid and wasteful and make me hate myself) or I’d keep them, knowing eventually I’d have to perform this menial task all over again. And because I am far too important and busy for button-sewing, I’d almost certainly put off that task for months, just like I had with the first button (which would also be stupid and make me hate myself — until I knuckled down and did it, as I’d just finally done with the first).

So, rather smugly, I set about reinforcing the other silk buttons one by one.

But there was another reason I kept sewing. One I was only able to admit to myself later. I’d become absorbed in the task, menial as it was, but on top of this, I was now curious to hear the last fifteen minutes of the tedious worthy radio program. The one about industrial decline, about the book I wouldn’t read and the series I wouldn’t watch.

So I re-threaded my needle and kept going, re-pricking myself in the process. I didn’t swear this time. I felt calmer, less irritable, having surrendered myself to the task at hand. As I sucked the blood from my finger tip, I continued listening to the stories of black waste sites, dead babies, the ghoulish Victorian treatment of foreign migrant workers and of vast empty ghost towns in China, make-work projects built by toiling, suffering workers but never inhabited for shelter.

Slowly, as I worked, a vague and tenuous connection formed in my mind between these ruined-metropolises and the tireless efforts of locals to save them and my own ham fisted attempt at mending. Just as my silk pyjamas would never be new again, these cities could never be restored to their former glory. The idea of total restoration and rebirth is folly, especially when it is the insatiable greed of industry that led to the ruin in the first place.

We can’t rescue the world by turning back time, but we can learn from our errors if we take the time to be accountable and examine them closely. We can slow down and shift our attention to the slow, devoted work of going back over things, reinforcing them if necessary, one silk button at a time. We can’t prevent the inevitable but we can stave it off temporarily with small efforts and acts of devotion. There is always something worth salvaging — fresh hope to be found in the ruins. Even the most tedious things are absorbing if you focus on them tenderly for long enough.

Nothing broken is ever past mending. The world is endlessly revealing itself in curious ways, even on a dreary Monday morning in mid-February.

My favourite spring pyjamas. Cashmere is for winter. The season is turning.

"We can’t rescue the world by turning back time, but we can learn from our errors if we take the time to be accountable and examine them closely. We can slow down and shift our attention to the slow, devoted work of going back over things, reinforcing them if necessary, one silk button at a time. We can’t prevent the inevitable but we can stave it off temporarily with small efforts and acts of devotion" - I absolutely love this Leah. It resonates so much. Things like this can also be a form of meditation. ❤️

In a similar vein of thought, I sally forth to shovels the walks, both ours and the neighbours, all subsumed under drifts of snow.. Usually I'm listening to something, not always worthy, but often enough it's a podcast or an interview, elaborating on the latest outrage by The Great Pumpkin or Drug Fraud our Premier. The inevitable feelings of outrage are energizing when faced with a boring and repetitive task but in truth, there is a sense of satisfaction when it's completed.